|

| Yutaka Sado & the Tonkünstler-Orchester Niederösterreich © Nick Boston |

Saturday, 15 March 2025

Classy Brahms ends a fine visit from Yutaka Sado and the Tonkünstler-Orchester

Friday, 9 August 2024

Beauty without the beast: BBC Philharmonic, Feldman and Bihlmaier at the BBC Proms

Anja Bihlmaier (conductor)

7.30pm, Thursday 8 August 2024

Royal Albert Hall, London

★★★

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

Encore:

Edward Elgar (1857-1934): Salut d’amour, Op. 12

Sarah Gibson (1995-2024): warp & weft

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897): Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98

Anja Bihlmaier conducts the BBC Philharmonic

© BBC/Andy Paradise

Beethoven:

'A highly engaging performance from Feldmann, producing a bright, lively tone and lyrical line throughout'.

'... a performance of great beauty, with strong orchestral playing from the woodwinds in particular, but missing bite at the more dramatic moments'.

Gibson:

'Bihlmaier steered the orchestra through the complex rhythms in a work full of interest and challenge'.

Brahms:

'Bihlmaier gave the opening, which launches without introduction, a watery flow, (think Smetana’s Vltava), setting the tone for a fluid reading'.

'Bihlmaier shaped the progress of the unfolding variations with a strong architectural sense'.

Read my full review on Bachtrack here.

Tuesday, 28 February 2023

CD Reviews - February 2023

The ensemble ZRI take their name from Zum Roten Igel, the 19th century Vienna coffee house that was a hub for many composers, such as Brahms and Schubert, but also many folk and gypsy musicians of the time, creating a musical melting pot of influences and ideas. Here, in Cellar Sessions, the five-piece ensemble, consisting of clarinet (Ben Harlan), violin (Max Baillie), cello (Matthew Sharp), accordion (Jon Banks) and santouri (a member of the dulcimer family) (Iris Pissaride), have embraced this idea of melding together classical repertoire with gypsy and folk material, but bringing that up to the present day, adding contemporary pop influences such as Donna Summer, Taylor Swift and Solange into the mix. This works remarkably well, with playful, dancing works such as Tokay by George Boulanger (1893-1958), and the swinging Horă din Budești by Aurel Gore (1928-1989), both Romanian violinists and arrangers, sitting alongside the ensemble’s take on classical works. They give a gloriously mysterious rendition of Schubert’s ethereal Andante from the Piano Trio No. 3, with a wonderful santouri introduction giving a nod to his nickname as the ‘Knight of the Cimbalom’, due to his fascination for Hungarian traditional music. From this introduction, Schubert’s slow movement emerges out of a gently pulsing rhythm, with burbling clarinet and sweet violin capturing the intensity of the original, and following some improvisatory exploration by the clarinet, low cello rumblings herald the return of the haunting sadness of the santouri. The Presto from Bach’s Violin Sonata No. 1 receives the ZRI treatment too, with the clarinet swinging the cross rhythms over gentle plucking from strings, building to some great rippling flourishes from the clarinet. Donna Summer’s I Feel Love opens with a bouncing accordion, but it’s the cello that sets up the iconic driving rhythm, whilst ethereal violin harmonics take on the melodic line. This all builds to a crazy clarinet riff, before a gradual fade. Taylor Swist’s Shake it Off is combined with a klezmer melody Lebedik un Freylach by Abe Schwartz (1881-1963), from a mournfully atmospheric beginning through to a racing, dancing conclusion. Matthew Sharp even gives us an expressive, cabaret-style baritone for Jay Gorney’s (1896-1990) Brother can you spare a dime?, with a shimmering accompaniment developing into swinging jazz. Brahms makes an indirect appearance, in the form of Isteni Csárdás by Miska Borzó (1800-1864), itself no doubt drawn from an older Hungarian tune, but better known to us now from Brahms’ Hungarian Dance No. 1, here full of the tune’s wildness and virtuosic energy in ZRI’s interpretation. They end with a delicate tango, Rote Rosen by Helmut Ritter (1907-1988), full of gentle nostalgia, before fading off into the distance. Overall, an extremely clever and inventive collection of repertoire, performed with joy and spirit throughout.

Greek-born pianist Alexandra Papastefanou studied in Moscow, Budapest and the US, and has had lessons from Alfred Brendel. She has performed all of Bach’s keyboard works, and recorded most of them too. Here she brings us a collection of transcriptions – so we’re immediately moving beyond the issue of performing his keyboard works on a modern piano, as here we have a trio sonata, chorales and cantatas, all in her own transcriptions, apart from Myra Hess’ famous arrangement of Jesus bleibet meine Freude (‘Jesu, joy of man’s desiring’), with which she ends her recording. Along the way, there are a couple of surprises too, with Papastefanou adding her own jazzy variation on top of her transcription of the chorale Allein Gott in der Höh sei Her, calling her addition appropriately Playing (with) Bach. The bouncy repeated figures here are effective, with the increasingly clashing harmonies providing an unusual counterpoint. We also get A Tribute to Bill Evans combined with An Wasserflussen Babylon (which also gives the album its title, Tears from Babylon). Here, she draws on Evans’ Peace Piece, with her own extemporisations entwined with the chorale melody in a particularly effective way, making this in fact the disc’s highlight for me. The Trio Sonata No. 5, BWV 529’s opening Allegro is clean, bright and lively, whilst the Largo that follows is tender and expressive. Papastefanou captures these contrasts throughout the recording, with joyful spirit for Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren, carefully bringing out the chorale melody from within the busy moving textures, whilst using a softer, more expressive tone for the Aria, Meine Seufzer, meine Tränen. The plodding bass line for Gott hat alles wohlgemacht from BWV35 works well, as does the energetic Sinfonia from BWV18. Ending with Myra Hess’ transcription is a fitting tribute to all those that have gone before, transcribing and arranging Bach’s music, and Papastefanou’s rendition of Hess’ classic is captivating. Throughout this collection, Papastefanou captures the essence of Bach’s music, whilst taking us in some new and unexpected directions too.

Wednesday, 28 December 2022

CD Reviews - January 2023

Various. 2022. Arc II. Orion Weiss. Compact Disc. First Hand Records FHR128.

The Mariani Klavierquartett return with the second release in their cycle pairing Brahms’ Piano Quartets with those of Friedrich Gernsheim (1839-1916). Gernsheim’s music suffered from a ban in Nazi Germany, and never really recovered, and it still deserves greater exposure than it receives, so this cycle is to be welcomed. In the first pairing, Gernsheim’s quartet stood alongside his friend’s admirably. Here, perhaps Gernsheim suffers a little next to Brahms’ mammoth A major Piano Quartet, Op. 26, weighing in at nearly 50 minutes. The opening movement is full of passion and is of epic proportions, yet the Marianis ensure there is a lightness of touch where needed, and Gerhard Vielhaber on piano never overly dominates the texture, which is also testament to the excellently balanced recording here. The piano is freed a little in the romance of the slow movement, with comments from the strings pulsing around it. Again, the Marianis achieve admirable lightness in the Scherzo, despite Brahms’ weighty approach, and they give the Finale energetic drive, with its stomping second beat rhythms, yet pull back expertly for the lighter moments, and the slowing train is beautifully judged before the final race to the end. Gernsheim’s Piano Quartet, Op. 47 is much lighter in mood, and the Marianis bring out the hints of ballroom swing in the opening movement. There is plenty of invention throughout, and galloping energy in the second movement is contrasted with warm lyricism. The slow movement is warm and lilting. Here Gernsheim ruminates on his melodic material to the point of slightly rambling, but the ending is sublimely touching nevertheless. The finale’s jaunty theme is treated to lots of fugal treatment and running accompaniments in its variations, with the piano in particular getting to show off with racing, cascading scale passages, and hefty chords are combined with more wild scales for the exuberant finish. Another illuminating release, and I look forward to the final volume.

Various. 2022. Brahms & Gernsheim Piano Quartets. Mariani Klavierquartett. Compact Disc. Audax Records ADX11202.

In the sixth volume of his survey, pianist Barry Douglas tackles the second set of Impromptus, D935 and the Piano Sonata in A minor, D845 by Schubert (1797-1828). The Sonata was the last of three in the same key, and the most substantial of these. Douglas takes a weighty approach here, giving the opening movement the heft of a Chopin Polonaise, emphasising the drama. His tempi throughout tend towards the slow side, and this holds up some of the second movement’s variations, yet there is a spring in his step for the third movement scherzo, and the finale has suitable wildness in places. For the Impromptus, the first has smoothly flowing hand crossing and bell-like tone at the top, but the second is taken at a very slow tempo indeed, which means that the central bubbling triplets lose their urgency, particularly for the plunge into the minor key for its second half, and the return of the opening is in danger of grinding to a halt. The Rosamunde-esque dance of the third has poise and delicacy, but again could benefit from a little more flowing tempo, although the tempo does pick up as the variations’ complexity increases, and by the end there is a delightful flow in the rapid motion of Schubert’s decorative writing. The fourth has incredibly virtuosic running scales, and Douglas takes this at a suitably furious lick, making me wish there had been more of this fire elsewhere. After the exuberance of this comes Liszt’s gloriously rich transcription of Schubert’s Ave Maria to finish, and Douglas gives this great warmth and expression, as well as effortless virtuosity. Overall, a mixed contribution to his otherwise exemplary Schubert survey so far.

Tuesday, 5 July 2022

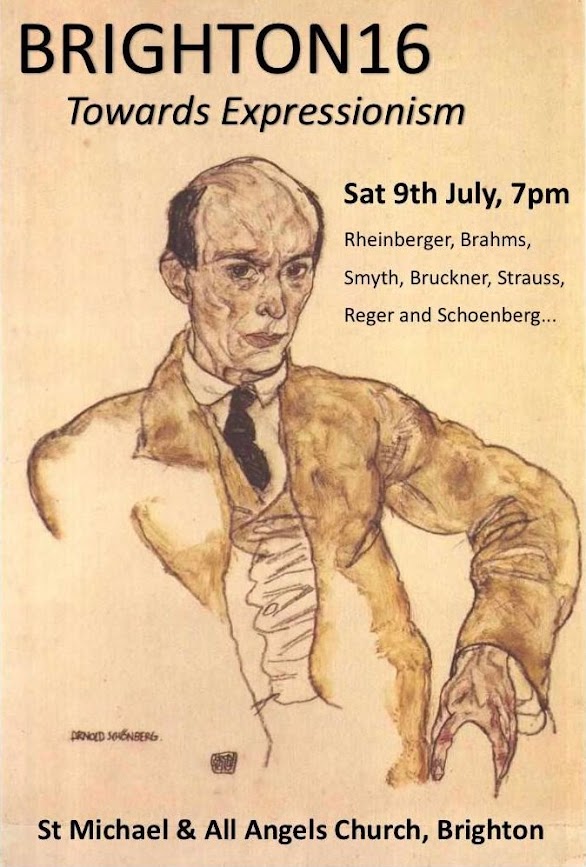

Brighton16 - Towards Expressionism - Saturday 9 July

Brighton16 will be singing music by Rheinberger, Brahms, Smyth, Bruckner, Reger, Schoenberg, and Strauss' 16-part anthem, Der Abend.

7pm, Saturday 9 July, St Michael & All Angels Church, Brighton

Entrance free

Thursday, 21 April 2022

Artistry, focus and virtuosic fireworks from Yuja Wang in recital

|

| Yuja Wang (© Ian Farrell) |

Wednesday, 23 June 2021

CD Reviews - June 2021

The Doric String Quartet are on their fourth volume of the String Quartets of Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), a cycle they began way back in 2014. Here, they play the six Op. 33 Quartets, nicknamed the ‘Russian quartets’, after their dedication to the Grand Duke Paul of Russia. As ever, the Doric’s performances are impeccable, and they are alive to the energy and fun in Haydn’s writing throughout. The Scherzo of No. 1 has real bite, accentuating the contrast with the seemingly light and delicate Andante that follows, and the finale is taken at a breathtaking lick without any loss of accuracy or detail. No. 2’s Scherzo has a real bounce, the first violinist Alex Redington enjoys the somewhat vulgar slides in the rustic Trio, and the Finale’s ‘joke’ (giving this quartet its nickname) ending is delightfully judged. They give No. 3’s strange Scherzo a dark, veiled tone which works incredibly well, and its Adagio is especially sweet by contrast, all swept away by the rustic dancing Rondo. They exploit the lyrical in No. 4’s Largo, and there’s another blisteringly quick Finale here. Redington makes No. 5’s aria-like Largo sing, and they all make great play of Haydn’s two/three confusions in the Scherzo, before the lightly dancing Allegretto finale, topped off with its crazily fast Presto coda. No. 6’s Andante gets a particularly tender reading here, and its finale is gently understated. The Dorics are clearly alive to the variety here, and not afraid to push tempi in the interest of keeping proceedings alive and vibrant, and they add another strong volume here to their survey.

The Paris based label Audax Records, established by violinist and director Johannes Pramsohler, continues to go from strength to strength, with 25 releases, many award-winning under their belt in just eight years. The latest release moves forward a little from the label’s general focus on the Baroque, with the Mariani Klavierquartett beginning a cycle pairing the Piano Quartets of Brahms (1833-1897) with those of a lesser-known composer, Friedrich Gernsheim (1839-1916). The two composers were friends, and Gernsheim was a particular champion of Brahms’ German Requiem, conducting the work on a number of occasions. Even though Gernshiem’s composing career began before Brahms’, he is often dismissed as being heavily influenced by his friend, and his work and reputation suffered from a subsequent ban in Nazi Germany owing to his Jewish heritage. The Mariani quartet’s recording project began in January 2020, but was of course immediately curtailed by the pandemic, so it is great that they have been able to return and complete this first volume, with a spirited and lively performance of Brahms’ Piano Quartet No. 1, Op, 25. Their opening movement draws the listener in immediately from the piano’s opening melody onwards. In the second movement, the cello propels things with constant quavers, whilst the violin and viola converse with the piano. The Mariani cellist, Peter-Philipp Staemmler keeps things moving without allowing his perpetual motion to get in the way of the other players’ conversations. The third movement is a masterpiece of Brahms’ lyricism and harmonic invention, and it is in secure hands here in this warmly sensitive performance, with some particularly warmly rippling playing from pianist Gerhard Vielhaber, and a vibrantly contrasting central section played with great spirit by all. The finale, ‘Rondo alla Zingarese’, with its typical Brahmsian take on Hungarian rhythms and melodies is taken at a great pace, with incredibly impressive virtuosity on display from all here, but once again, pianist Vielhaber deserves particular mention for his effortless dexterity throughout. Gernsheim’s Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 20 opens with a gloriously rich and flowing movement, and the Mariani players produce appropriately warm tones throughout. Gernsheim’s melodies flow effortlessly, and the full-on dramatic climaxes are powerfully delivered here, yet the Marianis also bring out the moments of delicate detail too. The second slow movement is a beautiful example of Gernsheim’s heartfelt lyricism, and like the slow movement of the Brahms, the Marianis play with deep assurance and sensitivity. The closing Rondo is lively and again packed with melodic ideas, as well as a dancing rhythmic pace. Here it has playful delicacy and energy, allowing for the contrast between the lighter, smaller scale moments and the high-spirited peaks to shine, building to a glorious finish. This is a highly impressive first volume, with assured Brahms coupled with illuminating Gernsheim, and I look forward to hearing more.

Tuesday, 25 May 2021

Sunny Dvořák and passionate Brahms from Nézet-Séguin and the Orchestre Métropolitain

|

| Yannick Nézet-Séguin © Hans Van der Woerd |

Yannick Nézet-Séguin (conductor)

Friday, 23 October 2020

Sunlit Brahms and fizzy Haydn on the south coast

|

| Stephen Hough, Mark Wigglesworth & the BSO © Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra |

Stephen Hough (piano)

Mark Wigglesworth (conductor)

★★★★