From the opening notes of Adriana González (soprano) and Iñaki Encina Oyón's new disc of the complete songs of Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909), I could tell this would be a treat. González's voice is warm and engaging, and the opening song, 'Besa el aura', is full of sensuality in its kisses (supposedly by the air, waves, flames and river...). There are no fewer than thirty songs here, and surprisingly for one of the most well-known Spanish composers, only this opening set, 'Rimas de Bécquer', is actually in Spanish. There are songs in Italian, French, and even English, and they are laid out in chronological order, showing Albéniz's development from aged 26 to his untimely death at the age of just 48. The songs also show his journey from Spain to life in London and then ultimately in Paris. There are common stylistic features - they are pretty much all set syllabically (one note per syllable), with expressively lyrical vocal lines, and the themes are familiar - lost love, the fragility of love, life and death, and visions in dreams and sleep, etc. Another surprise is that, for a composer known for his fiendish piano works, the piano accompaniments of the earlier songs are relatively simple, yet not without considerable interest. It is only in the later songs, such as 'Art thou gone forever, Elaine?' and 'The gifts of the Gods', and then the lush expressionism of the 'Deux morceaux de prose' that the piano has a more virtuosic role. Yet Oyón makes the most of the subtlety of interest in earlier songs too, particularly the lilting rhythm of the 'Barcarola' and increasingly expressive accompaniment to 'Il tuo sguardo', both from 'Seis baladas'. González can move effortlessly between simple romanticism ('Una rosa in dono') to extremes of despair ('¿De dónde vengo...?') and tender expression ('To Nellie'). She even gives us ever so slightly schmaltzy Victoriana in 'Will you be mine?'. But the final four songs (reordered here in the order Albéniz wrote them) are the most evocative, full of Spanish infused shifting harmonies and crying piano grace notes in the incredibly moving 'In sickness and health'. Oyón's virtuosic pianism comes to the fore here, and throughout González is a master of communicating the texts with wonderful dynamic control and variety of tone. Highly recommended.

Now for some reverse engineering, with 'The Ghost in the Machine'. In 18th century Europe, there was a fascination with all things mechanical, and musical instruments such as barrel organs and organ clocks that could reproduce music were highly popular. Of course, in the days before recording, they were a way in which people could hear again and again the popular works of the day. But what is also fascinating is how such instruments reveal 18th century tastes for performance of music, particularly in terms of ornamentation and decoration. Recorder player Emily Baines, also director and co-founder with lutenist Arngeir Hauksson of the ensemble Amyas, has transcribed music from such instruments, and has compared them with other sources such as recorder instruction books and arrangements. It turns out that more is more, and some of the renditions here of works by Handel, Arne, and even 'God Save the King' seem to have decoration on virtually every note. As a result, Arne's 'Rule Britannia', and 'God save the King' end up being much more playful and brighter, without the nationalistic fervour we're used to. Baine plays on a range of instruments, from the tenor through to the descant recorders, as well as the 'voice flute', a recorder that sits in range between the tenor and treble, and she is joined by Amyas, consisting of two violins, viola, cello, guitar/theorbo and organ/harpsichord. The transcribed works are drawn from a clock organ made in London by Charles Clay, Clockmaker to His Majesty's Board of Works, and a barrel organ made by Henry Holland. Clay's incredible clocks containing works of art and functioning organs could be seen in his workshop and the public could hear them play for a shilling. The disc here opens with a 'suite' of three popular pieces by Handel - the Overture to his Water Music, the Dead March from Saul, and 'See the Conquering Hero Comes' from Judas Macabeus. Instantly we are in a world of bright ornamentation on the recorder, with rippling harpsichord, strumming theorbo and lively strings. There is some contrast in the two 'Ornamented Airs & Brunettes' by Jacques Hotteterre le Romain (1673-1763) which follow, largely as a result of the airier tone of the voice flute. But these two pieces aside, the repertoire here is lively and full of birdlike trills, twiddles and turns throughout. So from the familiar Handel (we also get some movements from Rinaldo and a Minuet from Rodelinda, as well as a hybrid of a transcribed 'Organ Concerto' from the barrel organ and the very similar Recorder Sonata) to the more unfamiliar, such as Francesco Barsanti's (1690-1775) Recorder Sonata, this is a joyful collection, full of energy and interest throughout. There's even a smattering of the 18th century fashion for 'Scots' music, with The Lass of Patie's Mill, and Francesco Geminiani's (1687-1762) 'Auld Bob Morrice', with Baine demonstrating particularly impressive virtuosity on the descant when the variation takes off. Her effortless ornamentation throughout is also testament to her virtuosity, but also her deep knowledge of this repertoire and her success in rescuing that 'ghost' from the machine.

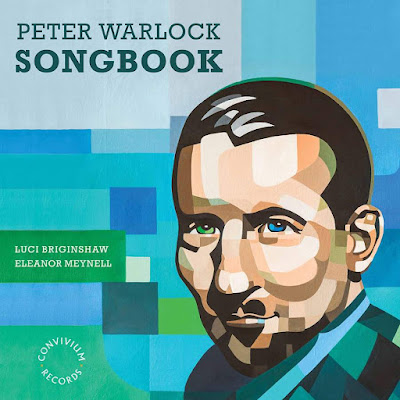

Peter Warlock (1894-1930) is probably best known for his Capriol Suite, The Curlew song cycle, or perhaps some of his boisterous drinking songs, but he wrote over 120 songs, as well as numerous choral pieces and works for voice and chamber ensembles. Warlock is in fact a pseudonym - his real name was Philip Heseltine, by which name he had a reasonably successful career as a writer and music critic. The pseudonym was perhaps to distance himself from his critical writings and save his own music from the acidic scrutiny he gave to others. Not formally trained as a musician, Delius became a mentor, although his own music moved away from his mentor's impressionistic style, towards a mix of folk and Elizabethan influences. Soprano Luci Briginshaw and pianist Eleanor Meynell have got together to record a significant selection of his songs - 28 in all for their new CD, the Peter Warlock Songbook. As with the Albéniz disc above, the songs are presented chronologically, but perhaps because they only span 13 years or so, the trajectory of development is not as marked. In fact, there is a remarkably coherent style evident, from his unique mix of early and folk influences, combined with daring use of chromaticism and crunching harmonies. Briginshaw's bright tone is well suited to the direct communication of many of the songs, yet she can also conjure up the frequent moments of wistful melancholy. Warlock is fond of lilting triple times (in more than half the songs here), from the tender My little sweet darling, with its nod back to Byrd, to Rest, sweet nymphs, in which the simple melody is disturbed by a mildly crunchy piano accompaniment, the opening The Everlasting Voices, with peeling piano and a mournful melody, and the darkly swinging Cradle Song. The early music influences are there in Lullaby, with its steady walking accompaniment, and the Dowland-esque Sleep, despite its unexpected, sliding harmonies. Briginshaw delivers the expressive melodies with soft tones, yet she also gives occasional more passionate outbursts full weight. Often, Warlock's piano parts provide chromatic edge but remain in the background, allowing the simple melodic lines to take centre stage. Meynell understands this and doesn't force the dark undertones through the texture. Yet when Warlock writes more virtuosic piano parts, such as in the passionate and watery Dedication, the playfully chirruping Spring and the highly virtuosic, rippling Consider, her playing shines through, making her restraint elsewhere all the more impressive. Highlights of the collection for me include the darkly sombre A Sad Song, with its lilting (again in three) but shifting harmonies and ranging melodic line, and the mysterious Autumn Twilight's winding accompaniment, with some captivating quiet singing from Briginshaw, also showing impressive control when Warlock challenges with final high sustained notes, such as in the darkly chanting The Night and And wilt thou leave me thus? All in all, an impressive display, showcasing another side to Warlock, as well as this talented duo.

No comments:

Post a Comment